Olbers' paradox

In astrophysics and physical cosmology, Olbers' paradox is the argument that the darkness of the night sky conflicts with the assumption of an infinite and eternal static universe. It is one of the pieces of evidence for a non-static universe such as the current Big Bang model. The argument is also referred to as the "dark night sky paradox". The paradox states that at any angle from the Earth the sight line will end at the surface of a star, so the night sky should be completely white. This contradicts the darkness of the night sky and leads many to wonder why we do not see only light from stars in the night sky (see physical paradox).

Contents |

History

Harrison's (1987) is the definitive account to date of the dark night sky paradox, seen as a problem in the history of science. According to Harrison, the first to conceive of anything like the paradox was Thomas Digges, who was also the first to expound the Copernican system in English and may have been the first to postulate an infinite universe with infinitely many stars. Kepler also posed the problem in 1610, and the paradox took its mature form in the 18th century work of Halley and Cheseaux. The paradox is commonly attributed to the German amateur astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, who described it in 1823, but Harrison shows convincingly that Olbers was far from the first to pose the problem, nor was his thinking about it particularly valuable. Harrison argues that the first to set out a satisfactory resolution of the paradox was Lord Kelvin, in a little known 1901 paper,[1] and that Edgar Allan Poe's essay Eureka (1848) curiously anticipated some qualitative aspects of Kelvin's argument:

Were the succession of stars endless, then the background of the sky would present us a uniform luminosity, like that displayed by the Galaxy – since there could be absolutely no point, in all that background, at which would not exist a star. The only mode, therefore, in which, under such a state of affairs, we could comprehend the voids which our telescopes find in innumerable directions, would be by supposing the distance of the invisible background so immense that no ray from it has yet been able to reach us at all.[2]

The Paradox

The paradox is that a static, infinitely old universe with an infinite number of stars distributed in an infinitely large space would be bright rather than dark.

To show this we divide the universe in to a series of concentric shells, 1 light year thick (say). Thus a certain number of stars will be in the shell 1,000,000,000 to 1,000,000,001 light years away, say. If the universe is homogeneous at a large scale, then there would be four times as many stars in a second shell between 2,000,000,000 to 2,000,000,001 light years away. However, the second shell is twice as far away, so each star in it would appear four times dimmer than the first shell. Thus the total light received from the second shell is the same as the total light received from the first shell.

Thus each shell of a given thickness will produce the same net amount of light regardless of how far away it is. That is, the light of each shell adds to the total amount. Thus the more shells, the more light. And with infinitely many shells there would be a bright night sky.

Dark clouds could obstruct the light. But in that case the clouds would heat up, until they were as hot as stars, and then radiated the same amount of light.

Kepler saw this as an argument for a finite observable universe, or at least for a finite number of stars. In general relativity theory, it is still possible for the paradox to hold in a finite universe:[3] though the sky would not be infinitely bright, every point in the sky would still be like the surface of a star.

The mainstream explanation

In order to explain Olbers' paradox, it is necessary to account for the relatively low brightness of the night sky in relation to the circle of our sun. The universe is only finitely old, and stars have existed only for part of that time. So, as Poe suggested, the Earth receives no starlight from beyond a certain distance, corresponding to the age of the oldest stars. Space is sufficiently rarefied that most lines from the Earth do not touch any star within this distance of Earth.

However, the Big Bang theory introduces a new paradox: it states that the sky was much brighter in the past, especially at the end of the recombination era, when it first became transparent. All points of the local sky at that era were brighter than the circle of the sun, due to the high temperature of the universe in that prehistoric era; and we have seen that most light rays will terminate not in a star but in the relic of the Big Bang.

This paradox is explained by the fact that the Big Bang Theory also involves the expansion of the "fabric" of space itself (not just the distance of objects in that space) that can cause the energy of emitted light to be reduced via redshift. More specifically, the extreme levels of radiation from the Big Bang have been redshifted to microwave wavelengths (1100 times lower than its original wavelength) as a result of the cosmic expansion, and thus form the cosmic microwave background radiation. This explains the relatively low light densities present in most of our sky despite the assumed bright nature of the Big Bang. The redshift also affects light from distant stars and quasars, but the diminution is only an order of magnitude or so, since the most distant galaxies and quasars have redshifts of only around 5 to 8.6.

Alternative explanations

Steady State

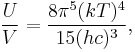

The redshift hypothesised in the Big Bang model would by itself explain the darkness of the night sky, even if the universe were infinitely old. The steady state cosmological model assumed that the universe is infinitely old and uniform in time as well as space. There is no Big Bang in this model, but there are stars and quasars at arbitrarily great distances. The light from these distant stars and quasars will be redshifted accordingly (by thermalisation), so that the total light flux from the sky remains finite. Thus the observed radiation density (the sky brightness of extragalactic background light) can be independent of finiteness of the Universe. Mathematically, the total electromagnetic energy density (radiation energy density) in thermodynamic equilibrium from Planck's law is

e.g. for temperature 2.7K it is 40 fJ/m3 ... 4.5×10−31 kg/m3 and for visible 6000K we get 1 J/m3 ... 1.1×10−17 kg/m3. But the total radiation emitted by a star (or other cosmic object) is at most equal to the total nuclear binding energy of isotopes in the star. For the density of the observable universe of about 4.6×10−28 kg/m3 and given the known abundance of the chemical elements, the corresponding maximal radiation energy density of 9.2×10−31 kg/m3, i.e. temperature 3.2K.[4] This is close to the summed energy density of the cosmic microwave background and the cosmic neutrino background. The Big Bang hypothesis, by contrast, predicts that the CBR should have the same energy density as the binding energy density of the primordial helium, which is much greater than the binding energy density of the non-primordial elements; so it gives almost the same result. But (neglecting quantum fluctuations in the early universe) the Big Bang would also predict a uniform distribution of CBR, while the steady-state model predicts nothing about its distribution. Nevertheless the isotropy is very probable in steady state as in the kinetic theory.

Thus, Olbers' paradox can not decide between a finite (e.g. some variants of the Big Bang model) and an infinite (Steady State theory or static universe) solution.

Finite age of stars

Stars have a finite age and a finite power, thereby implying that each star has a finite impact on a sky's light field density. But if the universe were infinitely old, there would be infinitely many other stars in the same angular direction, with an infinite total impact.

Absorption

An alternative explanation is that the universe is not transparent, and the light from distant stars is blocked by intermediate dark stars or absorbed by dust or gas, so that there is a bound on the distance from which light can reach the observer.

This would resolve the paradox given the following argument: According to the second law of thermodynamics, there can be no material hotter than its surroundings that does not give off radiation and at the same time be uniformly distributed through space, however there is no mathematical formula proving that light energy is absorbed infinitely and not radiated, especially by already highly heated particles of gas in a near vacuum. Energy must be conserved, per the first law of thermodynamics and it can be transformed. Therefore, the intermediate matter would not necessarily heat up or glow and the energy (possibly at different wavelengths) would dissipate in infrared radiation and various diffracted light shifted towards rend. This would not result in a paradox if current physics understanding is approaching the truth.

How bright would the sky be?

Suppose that the universe were not expanding, and always had the same stellar density; then the temperature of the universe would continually increase as the stars put out more radiation. Eventually, it would reach 3000K (corresponding to a typical photon energy of 0.3 eV and so a frequency of 7.5×1013 Hz), and the photons would begin to be absorbed by the hydrogen plasma filling most of the universe, rendering outer space opaque. This maximal radiation density corresponds to about 1.2×1017 eV/m3 = 2.1×10−19 kg/m3, which is nearly eleven orders of magnitude greater than the observed value of 4.7×10−31 kg/m3.[5] So the sky is about fifty billion times darker than it would be if the Universe were neither expanding nor too young to have reached equilibrium yet.

Fractal star distribution

A different resolution, which does not rely on the Big Bang theory, was first proposed by Carl Charlier in 1908 and later rediscovered by Benoît Mandelbrot in 1974. They both postulated that if the stars in the universe were distributed in a hierarchical fractal cosmology (e.g., similar to Cantor dust)—the average density of any region diminishes as the region considered increases—it would not be necessary to rely on the Big Bang theory to explain Olbers' paradox. This model would not rule out a Big Bang but would allow for a dark sky even if the Big Bang had not occurred.

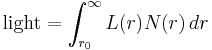

Mathematically, the light received from stars as a function of star distance in a hypothetical fractal cosmos is:

where:

r0 = the distance of the nearest star. r0 > 0;

r = the variable measuring distance from the Earth;

L(r) = average luminosity per star at distance r;

N(r) = number of stars at distance r.

The function of luminosity from a given distance L(r)N(r) determines whether the light received is finite or infinite. For any luminosity from a given distance L(r)N(r) proportional to ra,  is infinite for a ≥ −1 but finite for a < −1. So if L(r) is proportional to r−2, then for

is infinite for a ≥ −1 but finite for a < −1. So if L(r) is proportional to r−2, then for  to be finite, N(r) must be proportional to rb, where b < 1. For b = 1, the numbers of stars at a given radius is proportional to that radius. When integrated over the radius, this implies that for b = 1, the total number of stars is proportional to r2. This would correspond to a fractal dimension of 2. Thus the fractal dimension of the universe would need to be less than 2 for this explanation to work.

to be finite, N(r) must be proportional to rb, where b < 1. For b = 1, the numbers of stars at a given radius is proportional to that radius. When integrated over the radius, this implies that for b = 1, the total number of stars is proportional to r2. This would correspond to a fractal dimension of 2. Thus the fractal dimension of the universe would need to be less than 2 for this explanation to work.

This explanation is not widely accepted among cosmologists since the evidence suggests that the fractal dimension of the universe is at least 2.[6][7][8] Moreover, the majority of cosmologists take the cosmological principle as a given, which assumes that matter at the scale of billions of light years is distributed isotropically. Contrasting this, fractal cosmology requires anisotropic matter distribution at the largest scales.

Light incoherence

In May 2011, Pierre Blanc suggested an explanation which does not require any assumption on the size or age of the universe.

Any observation apparatus is restricted in the number of stars it can detect. If a device can detect only one star in a given (very small) cone, a better apparatus would see two stars; a still better one would see ten and so on. The first device “sees” one star as well as the combined light coming out of "unseen" or "undetected" stars. But the light signals sent by these “subliminar” stars are incoherent, in phase as well as in polarisation. Moreover, they are in large part reflected by less distant astronomical objects. Blanc shows that their combination results in a “background noise” with very little brightness, although the sky would appear less dark with more powerful instruments.[9]

References

- ^ For a key extract from this paper, see Harrison (1987), pp. 227–28.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan (1848). "Eureka: A Prose Poem". http://books.eserver.org/poetry/poe/eureka.html.

- ^ D'Inverno, Ray. Introducing Einstein's Relativity, Oxford, 1992.

- ^ Eddington's Temperature of Space

- ^ Unsöld, A.; Bodo, B. (2002). The New Cosmos, An Introduction to Astronomy and Astrophysics (5th ed.). Springer–Verlag. p. 485. ISBN 3-540-67877-8.

- ^ Joyce, M.; Labini, F.S.; Gabrielli, A.; Montouri, M.; Pietronero, L. (2005). "Basic Properties of Galaxy Clustering in the light of recent results from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey". Astronomy and Astrophysics 443 (11): 11–16. arXiv:astro-ph/0501583. Bibcode 2005A&A...443...11J. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053658.

- ^ Labini, F.S.; Vasilyev, N.L.; Pietronero, L.; Baryshev, Y. (2009). "Absence of sedlf-averaging and of homogeneity in the large scale galaxy distribution". Europhys.Lett. 86 (4): 49001. arXiv:0805.1132. Bibcode 2009EL.....8649001S. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/86/49001.

- ^ Hogg, David W.; Eisenstein, Daniel J.; Blanton, Michael R.; Bahcall, Neta A.; Brinkmann, J.; Gunn, James E.; Schneider, Donald P. (2005). "Cosmic homogeneity demonstrated with luminous red galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal 624: 54–58. arXiv:astro-ph/0411197. Bibcode 2005ApJ...624...54H. doi:10.1086/429084.

- ^ Blanc, Pierre “Le fond du ciel nocturne“, ScienceLib, 10 May 2011, 5 pp.

Further reading

- Edward Robert Harrison (1987) Darkness at Night: A Riddle of the Universe, Harvard University Press. Very readable.

- -------- (2000) Cosmology, 2nd ed. Cambridge Univ. Press. Chpt. 24.

- Taylor Mattie, Fundamentals of Heat Transfer. MAHS

- Wesson, Paul (1991). "Olbers' paradox and the spectral intensity of the extragalactic background light". The Astrophysical Journal 367: 399–406. Bibcode 1991ApJ...367..399W. doi:10.1086/169638.

External links

- Relativity FAQ about Olbers' paradox

- Astronomy FAQ about Olbers' paradox

- Cosmology FAQ about Olbers' paradox

- "On Olber's Paradox" at MathPages.com.

- Why is the sky dark? physics.org page about Olbers' paradox

- Why is it dark at night? A 60-second animation from the Perimeter Institute exploring the question with Alice and Bob in Wonderland